PLLR Drug Label Comparison Tool

Compare Old vs New Labeling

Select a drug to see how its pregnancy and lactation information would be presented under the old pregnancy letter system versus the new Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule (PLLR).

Before 2015, if you were pregnant and your doctor prescribed a medication, you might have seen a simple letter on the label: A, B, C, D, or X. That letter was supposed to tell you if the drug was safe. But it didn’t. Not really. A Category B drug might have had no human data at all. A Category C drug could have shown harm in animals but no proof in people. And yet, many doctors and patients treated B as safe and C as risky-even when the data said otherwise. The system was broken. That’s why the FDA replaced it with the Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule (PLLR).

What the PLLR Actually Replaced

The old pregnancy letter system had been around since the 1970s. It was simple, but dangerously oversimplified. A drug with no human studies got a C. A drug with a single case report of birth defects got a D. A drug proven to cause serious harm got an X. But here’s the problem: the categories didn’t explain why a drug was rated that way. They didn’t say how much of the drug crossed the placenta. They didn’t mention when during pregnancy the risk was highest. They didn’t talk about what happened if you stopped the drug. And they didn’t say anything about breastfeeding.The PLLR, finalized in December 2014, scrapped the letters entirely. Instead, it forced drugmakers to write clear, detailed narratives based on real data. This wasn’t just a formatting change. It was a cultural shift in how drug safety is communicated to providers-and ultimately, to patients.

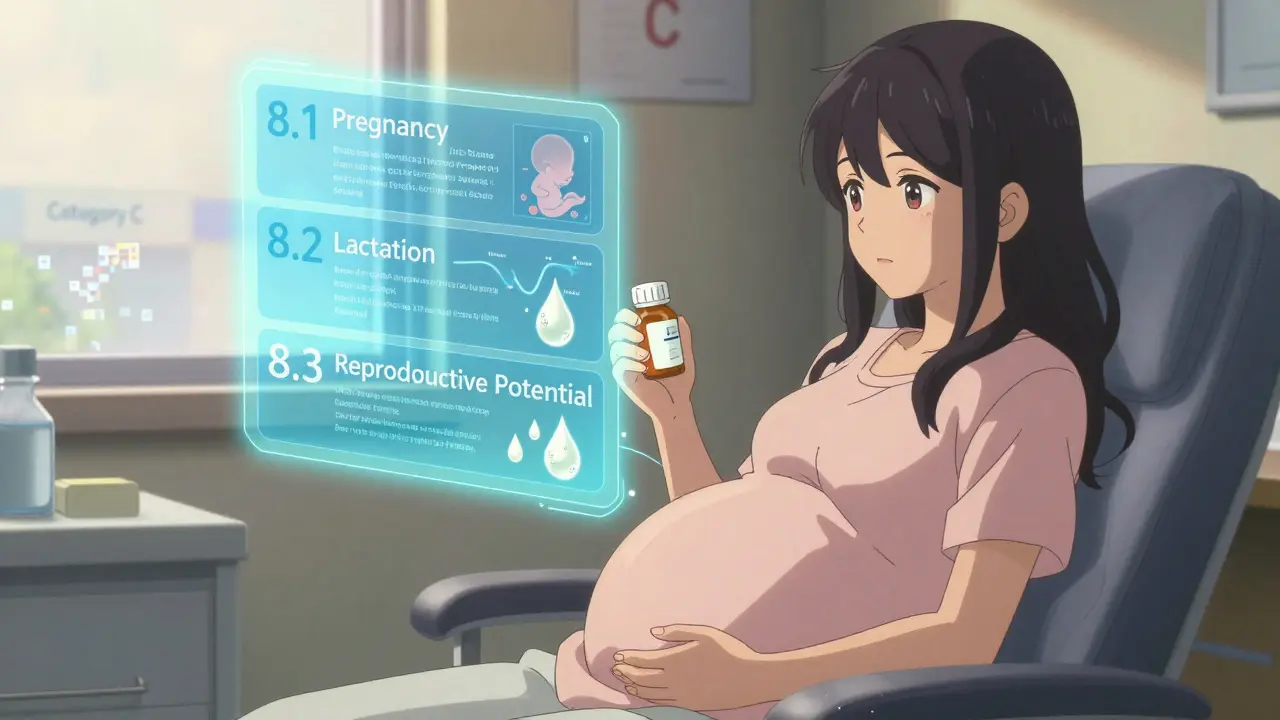

The Three New Sections You Need to Know

Under the PLLR, every prescription drug label now has three new subsections under Section 8: 8.1 Pregnancy, 8.2 Lactation, and 8.3 Females and Males of Reproductive Potential. Each follows the same three-part structure. Let’s break them down.8.1 Pregnancy: Risk Summary, Clinical Considerations, Data

The Risk Summary is the first thing you read. It doesn’t say “Category C.” It says: “Use of this drug during pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of oligohydramnios, which can lead to fetal lung hypoplasia and limb contractures.” Then it adds: “These effects were observed in 12% of exposed pregnancies in a cohort of 150 women.” The Clinical Considerations section answers practical questions: Should you stop the drug? When? What happens if you do? What if you can’t? For example, if a woman has epilepsy and needs to stay on her seizure medication, the label might say: “Discontinuation of this drug during pregnancy increases seizure frequency by 40%. The risk of uncontrolled seizures outweighs the potential fetal risk.” That’s the kind of nuance the old system never gave you. The Data section is where the evidence lives. It lists human studies, animal studies, and case reports. It tells you how many women were studied, what trimester they were exposed in, and what outcomes were measured. It doesn’t hide behind a letter. It shows you the numbers.8.2 Lactation: Milk Levels, Infant Exposure, and Breastfeeding Safety

The old system barely mentioned breastfeeding. The PLLR fixes that. The Lactation section now tells you:- How much of the drug gets into breast milk (as a percentage of the mother’s dose)

- Whether the infant’s blood levels are measurable

- Any reported effects on the baby-like drowsiness, poor feeding, or liver enzyme changes

- Whether the drug affects milk production

For example, a label might say: “Maternal serum levels of this drug are 12 ng/mL. Breast milk concentrations average 0.8 ng/mL. Infant daily intake is estimated at 0.003% of the maternal dose. No adverse effects have been reported in 200 exposed infants.” That’s actionable. That’s useful. That’s not a letter.

8.3 Females and Males of Reproductive Potential: Prevention, Testing, and Contraception

This section didn’t exist before. Now it’s mandatory. It answers: Does this drug cause birth defects? Then you need to know: Do you need a pregnancy test before starting? Do you need to use two forms of birth control? Does this drug interact with your birth control pills? Does it affect fertility?For drugs that cause severe birth defects, the label might say: “Pregnancy must be excluded within 7 days before starting. Two forms of contraception are required during treatment and for 1 month after. This drug reduces the effectiveness of hormonal contraceptives. Use a non-hormonal method such as an IUD or barrier method.”

This section is especially important for men. Some drugs can affect sperm and cause birth defects even if the woman isn’t taking the drug. The PLLR now requires that info to be included.

Why the Old System Failed

The letter system created false assumptions. A drug with no human data was labeled B-“no evidence of risk.” But that didn’t mean it was safe. It meant no one had studied it. Meanwhile, a drug with clear risks in animals but no human data was labeled C-“risk cannot be ruled out.” But many doctors interpreted that as “probably okay.”One study found that 60% of obstetricians misclassified drugs based on the old letters. They thought Category B drugs were safer than Category C, even when the Category C drug had better human safety data. The PLLR fixes that by forcing transparency. You can’t hide behind a letter anymore. You have to explain the risk.

What’s Missing? What’s New?

The PLLR didn’t just add information-it removed misleading elements. The FDA removed standardized risk statements like “risk outweighs benefit” because those phrases were just as vague as the letters. They also removed the separate “Nursing Mothers” and “Labor and Delivery” sections, folding them into the new structure where they belong.What’s new? Pregnancy exposure registries. Before, these were optional. Now, if a drug has a known or suspected risk, the label must include a link or contact info for a registry that tracks outcomes in pregnant women taking that drug. That’s how we learn. That’s how we improve.

Another big change: labels must be updated when new data comes in. The old system let outdated labels sit for years. Now, if a new study shows a risk, the manufacturer has to update the label within a year. That’s accountability.

Real-World Impact

In the U.S., about 6 million pregnancies happen every year. Nearly 90% of pregnant women take at least one prescription drug. Some take five or more. That’s not rare. It’s normal.Before the PLLR, doctors often avoided prescribing anything during pregnancy. Now, they have the tools to make better decisions. A woman with bipolar disorder might have been told to stop her mood stabilizer. Now, her doctor can read the label: “Discontinuation increases relapse risk by 70%. Fetal risk is low with lithium at therapeutic levels, but requires monitoring for cardiac defects.” That’s not fear. That’s balance.

For breastfeeding mothers, the PLLR has made it easier to continue treatment. A drug once labeled “avoid during lactation” might now say: “Infant exposure is less than 0.1% of maternal dose. No adverse effects reported in 150 infants.” That’s permission to breastfeed safely.

What’s Not Covered

The PLLR applies only to prescription drugs and biological products approved after June 30, 2001. Over-the-counter meds, supplements, and older drugs approved before 2001 are not required to follow it-though many have updated voluntarily. Also, the rule doesn’t cover vaccines or medical devices.And while the PLLR is a huge step forward, it’s not perfect. Some labels still lack data. If a drug has never been studied in pregnant women, the Risk Summary might say: “No human data available. Animal studies show fetal toxicity.” That’s honest. But it’s not comforting. That’s why registries matter-they fill the gaps.

How to Use This Information

If you’re a patient:- Ask your doctor to show you the updated drug label for any medication you’re taking during pregnancy or breastfeeding.

- Don’t rely on memory or old advice. Labels change.

- If you see a pregnancy registry listed, consider enrolling. Your data helps other women.

If you’re a provider:

- Read the Risk Summary first. Then the Clinical Considerations. Then the Data.

- Don’t assume a drug is safe just because it’s “Category B” in your old reference book.

- Use the label to guide conversations-not to scare, but to inform.

Where to Find PLLR Labels

The FDA’s website has a searchable database of drug labels. Go to DailyMed and search for any drug. Look for Section 8. You’ll see the new structure clearly labeled. You can also find comparison tools there that show the old letter system side-by-side with the new narrative format.Drug manufacturers also update their prescribing information on their websites. If you’re unsure, ask your pharmacist for the most current label.

International Differences

The U.S. isn’t alone in updating pregnancy labeling. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) has its own system. But a 2023 study found that in 68% of cases, the FDA and EMA used different language to describe the same drug’s risk. One might say “risk is possible,” the other might say “risk is probable.” That’s confusing for patients and providers who travel or get care across borders.There’s no global standard yet. But the PLLR is now the most detailed and clinically useful system in the world. Other countries are watching. Some are starting to adopt similar formats.

What’s Next for PLLR?

The FDA continues to refine how labels are written. New guidance documents are released every year. More drugs are being added to pregnancy registries. Real-world data from those registries is already improving safety-for example, by identifying which doses are safest in each trimester.Eventually, the goal is to make this information available in patient-friendly language-not just for doctors. But for now, the PLLR gives healthcare providers the tools to make better decisions. And that’s a win for every pregnant woman, every breastfeeding mother, and every child who benefits from safer, smarter care.

What replaced the FDA pregnancy letter categories (A, B, C, D, X)?

The Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule (PLLR), implemented by the FDA in December 2014, replaced the old letter categories with detailed narrative sections under Section 8 of drug labels: 8.1 Pregnancy, 8.2 Lactation, and 8.3 Females and Males of Reproductive Potential. Each section includes a Risk Summary, Clinical Considerations, and Data subsections to provide clear, evidence-based information instead of vague letters.

Does the PLLR apply to all medications?

No. The PLLR applies only to prescription drugs and biological products approved by the FDA after June 30, 2001. Older drugs approved before that date were required to remove the old letter categories by 2017, but they aren’t required to fully adopt the new narrative format unless they undergo a labeling change. Over-the-counter drugs, supplements, vaccines, and medical devices are not covered by the PLLR.

How does the PLLR help breastfeeding mothers?

The Lactation section (8.2) of the PLLR provides specific data on how much of the drug passes into breast milk, whether it affects milk production, and any known effects on the infant. For example, it might state that infant exposure is less than 0.1% of the mother’s dose with no reported side effects in over 150 cases. This replaces outdated warnings like “avoid during breastfeeding” with science-based guidance that supports safe nursing.

Why is the Pregnancy Testing section important?

The Pregnancy Testing subsection (part of Section 8.3) ensures that women are tested for pregnancy before starting drugs that could cause serious birth defects. This allows providers to delay treatment or switch to safer alternatives if needed. For example, drugs that cause neural tube defects may require a negative pregnancy test within 7 days before starting and monthly testing during use.

Can I trust the information on drug labels?

Yes-more than ever. The PLLR requires manufacturers to base their labeling on real data from human studies, animal studies, and post-marketing reports. Labels must be updated within a year of new safety information becoming available. Additionally, pregnancy exposure registries collect real-world outcomes, helping to validate and improve label accuracy over time. Always check the most current label on DailyMed or ask your pharmacist for the latest version.

Colleen Bigelow

December 16, 2025 AT 04:44So now the FDA makes drug companies write essays instead of just saying 'DANGER' or 'probably fine'? LOL. I bet this is just another bureaucratic power grab so Big Pharma can bury the real risks in 12 pages of legalese. You think a pregnant woman is gonna read all that? Nah. She's gonna Google it and end up on a Reddit thread where some guy says 'my cousin took this and her kid had three heads' and that's what she believes now. 😏

Billy Poling

December 18, 2025 AT 03:43While I acknowledge the theoretical merits of the Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule as a paradigmatic shift toward evidence-based pharmacovigilance, I must express profound concern regarding the practical implementation of this regulatory framework. The cognitive load imposed upon the average clinical provider-particularly those in resource-constrained environments-is not trivial. Moreover, the absence of standardized risk quantification metrics introduces significant interpretive variability, which may inadvertently exacerbate clinical indecision. The narrative format, while linguistically rich, lacks the heuristic efficiency of categorical systems, thereby potentially delaying therapeutic intervention in time-sensitive obstetric scenarios.

Dave Alponvyr

December 19, 2025 AT 07:12Letters were dumb. This is way better. No more guessing. Just facts.

Cassandra Collins

December 21, 2025 AT 02:54ok but i heard the fda is hiding something… like, the real reason they changed it is because they got caught letting pharma lie about autism links in the 90s and now they’re trying to look good? i mean, why now? why not 20 years ago? 🤔 #conspiracy #fda #pregnancydrugs

Mike Smith

December 22, 2025 AT 22:17This is one of the most important changes in modern maternal healthcare. For too long, we’ve treated pregnant patients as if they were medical anomalies instead of people who deserve clear, compassionate, evidence-based guidance. The PLLR doesn’t just inform-it empowers. Providers can now have real conversations. Patients can make informed choices. And for the first time, we’re including men in the conversation about reproductive safety. That’s not just policy. That’s progress.

Ron Williams

December 23, 2025 AT 02:34Been reading these new labels for a while now. Honestly? They’re way more useful than the old letters. I’m a pharmacist in rural Ohio, and I’ve had moms come in crying because their OB told them ‘no meds’-then we pull up the label and it says ‘no known risk, 200+ babies exposed, zero issues.’ That changes everything. Still a few labels are light on data, but at least now we know what we don’t know. And that’s better than pretending we do.

Kitty Price

December 24, 2025 AT 20:55YESSSS this is so much better!! 🙌 I was terrified to take my anxiety med while pregnant and the old label just said ‘C’-so I quit cold turkey and had a panic attack in the grocery store. The new label said ‘infant exposure minimal, no reported sedation’ and my doc actually helped me stay on it. Thank you, FDA, for not being dumb. 💕

Aditya Kumar

December 26, 2025 AT 06:42Too much reading. I just ask my doctor.