What Exactly Is a Prolactinoma?

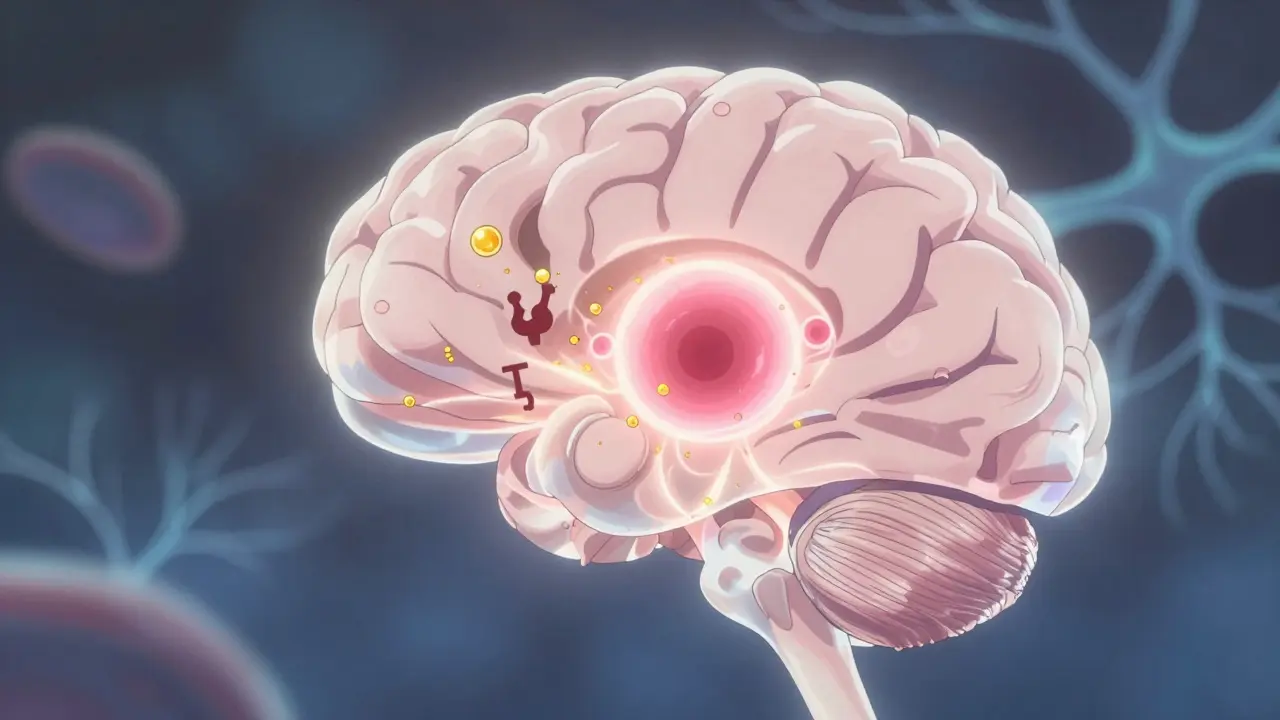

A prolactinoma is a benign tumor in the pituitary gland that makes too much prolactin - a hormone that normally triggers milk production after childbirth. It’s the most common type of hormone-producing pituitary tumor, making up 40% to 60% of all pituitary adenomas. While these tumors are not cancerous, they can cause serious problems by flooding your body with excess hormones or pressing on nearby nerves and brain structures.

Most people with prolactinomas don’t even know they have one until symptoms show up. About 1 in 10 adults have some kind of pituitary tumor, but only a small fraction cause noticeable issues. Prolactinomas come in two sizes: microadenomas (under 1 cm) and macroadenomas (over 1 cm). The bigger ones are more likely to cause vision problems or headaches because they push against the optic nerve.

How Prolactin Disrupts Your Body

Prolactin isn’t just about breastfeeding. In men and non-pregnant women, it helps regulate sex hormones. When levels go too high, it shuts down the normal production of estrogen and testosterone. That’s why women with prolactinomas often stop getting their periods (amenorrhea), have trouble getting pregnant, or produce breast milk even when they’re not nursing (galactorrhea). About 95% of women with untreated prolactinomas experience one or more of these symptoms.

Men don’t get galactorrhea, but they do suffer. Low testosterone means reduced libido, erectile dysfunction, and sometimes breast enlargement. Many men also feel tired, lose muscle mass, or notice a drop in body hair. Because these symptoms are easy to ignore or blame on stress, men often go years without diagnosis. In fact, men are more likely to be diagnosed with larger tumors because their symptoms develop slower.

High prolactin doesn’t just affect reproduction. It can lead to bone thinning over time due to low sex hormones. Some people develop mood swings, depression, or trouble concentrating - not because the tumor is pressing on the brain, but because hormones are out of balance.

How Doctors Diagnose It

Diagnosis starts with a blood test. If your prolactin level is above 150 ng/mL, there’s a 95% chance it’s a prolactinoma. Levels over 200 ng/mL usually mean the tumor is larger than 1 cm. But don’t jump to conclusions - some medications (like antidepressants or antipsychotics), kidney failure, or even pregnancy can raise prolactin. Your doctor will rule those out first.

The next step is an MRI of the pituitary gland. A high-resolution scan with 3mm slices is needed to see small tumors. If the tumor is bigger than 1 cm, you’ll also get a visual field test. This checks if your peripheral vision is affected - a sign the tumor is pressing on the optic nerve. Without this test, you might not realize your vision is slowly fading until it’s too late.

Doctors don’t just look at size and hormone levels. They check if the tumor is invasive - meaning it’s growing into nearby structures like the cavernous sinus. That affects treatment choices. A tumor that’s stuck to major blood vessels or nerves is harder to remove surgically.

First-Line Treatment: Dopamine Agonists

For almost everyone with a prolactinoma, the first treatment is a pill - not surgery. Dopamine agonists like cabergoline and bromocriptine trick the tumor into stopping prolactin production. Cabergoline is now the go-to because it works better and has fewer side effects.

Cabergoline is usually started at 0.25 mg twice a week. If prolactin levels don’t drop after a few weeks, the dose is slowly increased. Most people see prolactin levels return to normal within 3 months. Tumor shrinkage follows - about 85% of microadenomas and 70% of macroadenomas get smaller. Many women get their periods back, and men regain sexual function.

Side effects are usually mild: nausea, dizziness, or headaches, especially when starting. These often fade after a few weeks. Only about 18% of people stop cabergoline because of side effects - compared to 32% who quit bromocriptine. Bromocriptine needs to be taken daily and causes more stomach upset.

Here’s the catch: you usually have to take these pills for years, sometimes for life. Stopping too soon causes prolactin to spike again within 72 hours. About 70% of patients need ongoing treatment. But for many, the trade-off is worth it - no surgery, no radiation, and a return to normal life.

Surgery: When Pills Aren’t Enough

Surgery is reserved for cases where medication doesn’t work, causes intolerable side effects, or when the tumor is so big it’s threatening your vision. The standard approach is transsphenoidal surgery - a minimally invasive procedure where the surgeon reaches the pituitary through the nose. Endoscopic tools give a clear view and reduce recovery time.

Success rates depend heavily on tumor size. For microadenomas, surgeons remove the tumor completely in 85-90% of cases. For macroadenomas, it drops to 50-60%. Even when the tumor looks gone on scan, some cells may remain - leading to recurrence in 25-30% of larger tumors within five years.

Immediate risks include CSF leaks (2-5%), temporary diabetes insipidus (5-10%), and bleeding in the pituitary (1-2%). Most patients go home in 3-5 days. Recovery is quick, but hormone levels can take weeks to stabilize. Some people need hormone replacement therapy afterward if the pituitary gets damaged.

Dr. Edward Laws from Brigham and Women’s Hospital says surgery should be for those who can’t tolerate pills or have vision loss - not as a first choice. For most, medication is safer and just as effective.

Radiation: The Slow Option

Radiation is rarely the first option. It’s used when tumors come back after surgery and meds don’t work. It’s slow - it can take 2 to 5 years to lower prolactin levels. But it’s useful for tumors that can’t be fully removed or are growing back.

There are three types: conventional radiation (given over 5-6 weeks), Gamma Knife radiosurgery (one high-dose session), and proton beam therapy. Gamma Knife is now preferred because it targets the tumor precisely, sparing the optic nerve and brain tissue. It controls tumor growth in 95% of cases at five years, with only 1-2% risk of vision damage.

The downside? Radiation often causes the pituitary to stop working over time. About 30-50% of patients develop hypopituitarism - meaning they need lifelong hormone replacement for cortisol, thyroid, or sex hormones. That’s why doctors avoid it in younger patients unless absolutely necessary.

What Life Looks Like After Diagnosis

Most people with prolactinomas live normal lives. With treatment, symptoms reverse. Women get pregnant. Men regain energy and sex drive. Vision improves. Bone density slowly recovers.

But you can’t stop monitoring. Even if your prolactin is normal, you need blood tests every 3 months at first, then once a year. MRIs are repeated every 1-2 years, especially if you’re on medication. Missing a dose of cabergoline can cause a rebound in prolactin and tumor regrowth.

Long-term use of cabergoline (more than 2.5 mg per week for over 3 years) carries a small risk of heart valve problems. The European Society of Endocrinology recommends an echocardiogram every two years if you’re on high doses. The FDA has a black box warning for this, but the risk is low in most patients.

Some people feel anxious about needing lifelong meds. But compared to the alternatives - surgery with its risks, or radiation that slowly destroys your hormone system - daily pills are the least disruptive option.

What’s Next in Treatment?

Research is moving fast. A new drug called paltusotine, approved for acromegaly, is now being tested for prolactinomas. Early results show it lowers prolactin without the nausea of dopamine agonists. Gene therapies targeting mutations like MEN1 are in early trials. AI is being used to predict which tumors will grow or resist treatment based on their molecular profile.

One big shift is happening: doctors are starting to classify tumors not just by size, but by their genetic makeup. Some tumors have mutations that make them more aggressive or more responsive to certain drugs. Within five years, treatment may be personalized - not just based on prolactin levels, but on your tumor’s DNA.

For now, though, the standard remains: test, treat with cabergoline, monitor closely. Most people respond beautifully. The goal isn’t just to shrink the tumor - it’s to restore your life.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can a prolactinoma cause infertility?

Yes, high prolactin levels suppress ovulation in women and lower sperm production in men. In fact, infertility is one of the most common reasons people are diagnosed. But with treatment, fertility often returns. Many women conceive within months of starting cabergoline. Men also see improved sperm counts and testosterone levels. If pregnancy doesn’t happen after treatment, other fertility causes should be checked.

Is cabergoline safe during pregnancy?

Yes, and it’s often continued during early pregnancy to prevent tumor growth. Prolactinomas can grow rapidly during pregnancy due to hormonal changes. Cabergoline is considered safe in the first trimester and is typically stopped once pregnancy is confirmed, unless the tumor is large or invasive. Your endocrinologist will monitor you closely. Most women with treated prolactinomas have healthy pregnancies.

Why do some people need lifelong treatment?

In many cases, the tumor doesn’t disappear completely - it just shrinks and becomes inactive. Stopping medication allows prolactin to rise again, and the tumor often grows back. About 70% of patients need to stay on low-dose cabergoline long-term. Some people try to stop after 2-3 years, but only about 30% remain in remission. Lifelong treatment isn’t a failure - it’s a manageable condition.

Can a prolactinoma turn into cancer?

No. Prolactinomas are benign. They don’t spread to other organs or become malignant. The danger comes from their size or hormone effects, not cancer. Even large tumors that invade nearby structures are still non-cancerous. There are extremely rare cases of pituitary carcinomas, but they’re not linked to prolactinomas.

What happens if I miss a dose of cabergoline?

Missing one dose usually won’t cause immediate problems, but prolactin levels can rise within 72 hours. If you miss a dose, take it as soon as you remember - unless it’s close to your next scheduled dose. Don’t double up. Consistent dosing is key to keeping prolactin low and the tumor from growing. Set phone reminders or use a pill organizer.

What to Do Next

If you’re experiencing irregular periods, low libido, unexplained milk production, or vision changes - get your prolactin tested. Don’t wait for symptoms to get worse. Early diagnosis means simpler treatment.

If you’ve been diagnosed, stick with your treatment plan. Don’t stop medication without talking to your doctor. Keep your follow-up appointments. Ask about genetic testing if your tumor is large or recurring. Join a patient support group - many find comfort and practical tips from others who’ve been there.

Pituitary adenomas aren’t rare. They’re manageable. With the right care, you don’t have to live with hormone chaos. You can get back to feeling like yourself again.

Becky M.

February 2, 2026 AT 01:25jay patel

February 4, 2026 AT 00:03Ansley Mayson

February 5, 2026 AT 10:13Hannah Gliane

February 7, 2026 AT 03:29Murarikar Satishwar

February 7, 2026 AT 03:55Ellie Norris

February 7, 2026 AT 08:30Marc Durocher

February 8, 2026 AT 09:14clarissa sulio

February 10, 2026 AT 03:38Monica Slypig

February 10, 2026 AT 17:29Vatsal Srivastava

February 11, 2026 AT 07:31