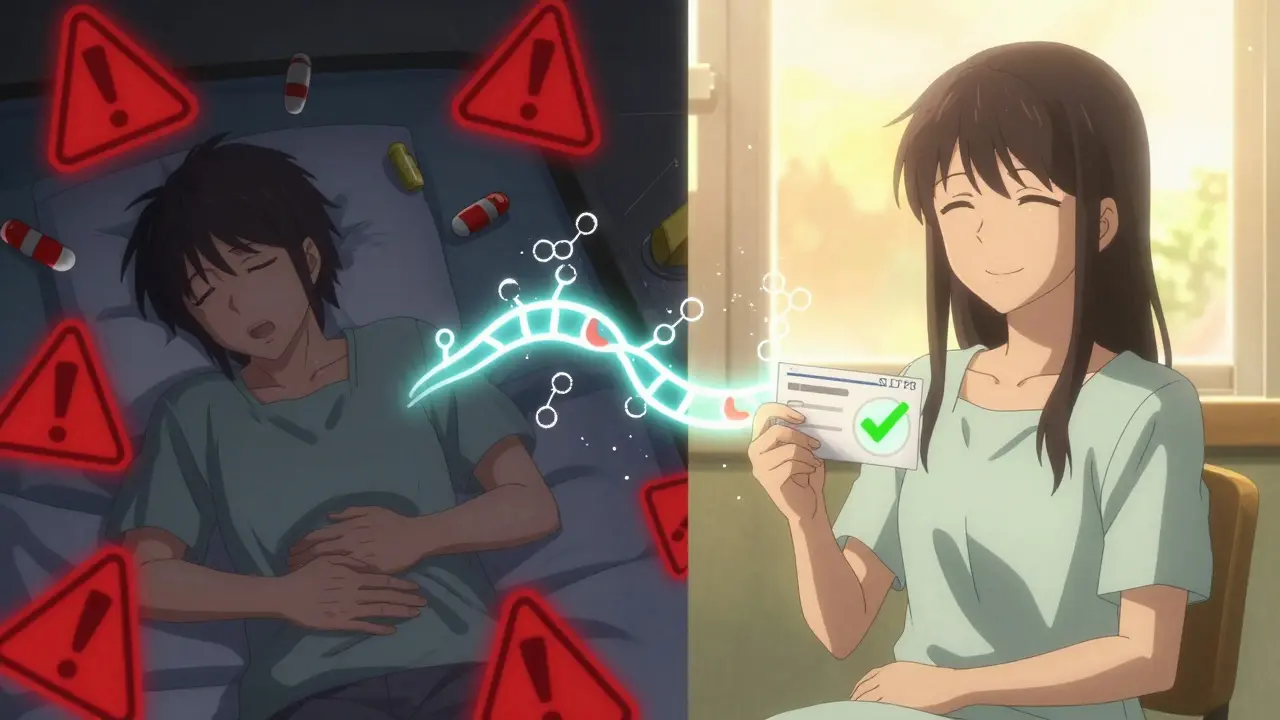

Every year, millions of people take medications that don’t work for them-or worse, make them sick. It’s not because they’re noncompliant or the doctor made a mistake. It’s because their genes affect how their body processes those drugs. This is where pharmacogenomics comes in: the science of using your DNA to predict how you’ll respond to medication. No more guessing. No more trial and error. Just the right drug, at the right dose, from day one.

Why Your Genes Matter When You Take a Pill

Your body doesn’t treat every pill the same. Two people taking the same antidepressant, for example, might have completely different outcomes. One feels better in weeks. The other feels worse-nauseous, dizzy, even suicidal. Why? Because of genes like CYP2D6 and CYP2C19. These genes code for liver enzymes that break down over 70% of commonly prescribed drugs. Some people are fast metabolizers. Others are slow. A few are ultra-rapid. And if your doctor doesn’t know which category you fall into, they’re prescribing blind.Take codeine. It’s a common painkiller, but it only works if your body converts it to morphine using the CYP2D6 enzyme. If you’re a slow metabolizer, you get no pain relief. If you’re an ultra-rapid metabolizer, your body turns too much codeine into morphine too fast. That’s how babies have died after breastfeeding from mothers on codeine. That’s why the FDA now warns against codeine use in children and recommends genetic testing before prescribing it to adults.

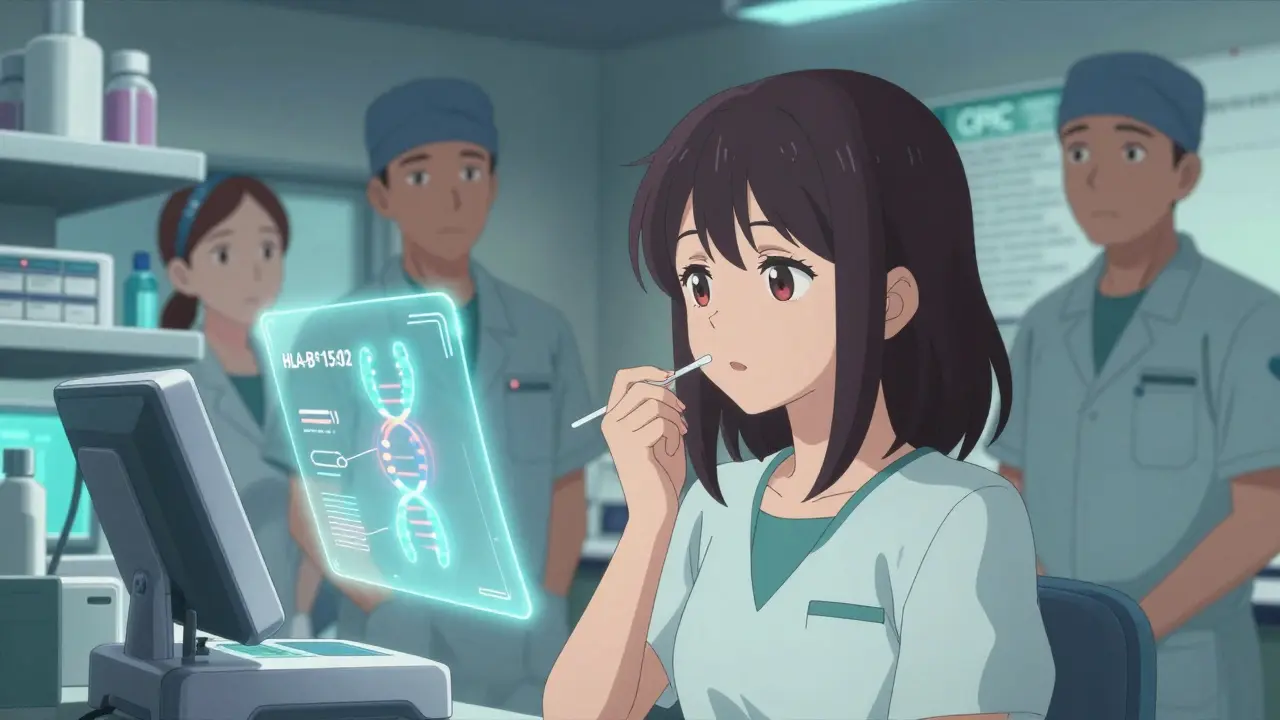

What Pharmacogenomic Testing Actually Measures

Pharmacogenomic testing looks at specific genes linked to how your body absorbs, breaks down, and responds to drugs. The most common genes tested are CYP2D6, CYP2C19, CYP2C9, and HLA-B. These aren’t random picks. They’re backed by decades of research and clinical guidelines from the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC).Testing is simple. A saliva swab, a blood draw, or even a cheek swab is all it takes. Results come back in about a week. The test doesn’t look at your entire genome. It focuses on 20-30 key genes that have proven, actionable links to drug response. For example:

- CYP2D6: Affects 25% of all prescription drugs, including antidepressants, beta-blockers, and opioids.

- CYP2C19: Impacts clopidogrel (Plavix), used after heart stents, and antidepressants like citalopram and sertraline.

- HLA-B*15:02: A genetic marker that increases the risk of life-threatening skin reactions from carbamazepine (Tegretol) in people of Asian descent.

These aren’t theoretical risks. They’re real, measurable, and preventable. The FDA has updated labels for over 28 drugs to include pharmacogenomic information. For abacavir (used in HIV treatment), testing for HLA-B*57:01 is mandatory before prescribing. Skip the test, and you risk a deadly allergic reaction.

Real Results: When Genetics Changed Treatment

Consider the case of a 52-year-old woman in Sydney who’d been on five different antidepressants over 15 years. None worked. She felt worse with each one. Her psychiatrist finally ordered a pharmacogenomic test. Results showed she was an ultra-rapid metabolizer of CYP2D6. That meant her body broke down paroxetine and fluoxetine too fast-before they could work. Her doctor switched her to bupropion, which doesn’t rely on CYP2D6. Within eight weeks, her depression lifted. No more hospital visits. No more side effects. Just relief.Another patient, a 38-year-old man on codeine for chronic back pain, had been vomiting for months. He thought it was the pain medication. His pharmacist suggested a CYP2D6 test. He was a slow metabolizer. Codeine wasn’t turning into morphine at all. His pain wasn’t being treated. He was just nauseous. Switching to tramadol-another painkiller not reliant on CYP2D6-eliminated his nausea and gave him real pain control.

These aren’t rare stories. A 2022 JAMA Psychiatry meta-analysis found that when doctors used pharmacogenomic testing to guide antidepressant prescriptions, patients were 30.8% more likely to go into remission than those on standard care. That’s a 66% increase in success rates. The number needed to treat? Just 8.2. Meaning, for every eight people tested and switched based on results, one person avoids months of suffering.

The Catch: Why It’s Not Everywhere Yet

You might think, if this works so well, why isn’t every doctor ordering these tests? The answer is messy. First, the science isn’t equally strong for all drugs. Only about 15-20% of commonly prescribed medications have clear, actionable genetic guidance. That’s improving-by 2027, that number could jump to 50%. But right now, your doctor might test you for antidepressants and get useful data. But if you’re on a blood pressure pill, the evidence might still be too weak to change practice.Then there’s the system. Only 37% of hospitals in the U.S. and Australia have successfully integrated pharmacogenomic results into their electronic health records. That means even if you get tested, your doctor might not see the results. Or they might not know how to interpret them. A 2022 survey found 68% of pharmacists needed extra training to confidently use PGx data. It’s not just about the test-it’s about the whole system catching up.

And insurance? It’s a patchwork. In oncology, nearly 90% of private insurers cover PGx testing. For psychiatric drugs, it’s only 47%. For heart medications? Even less. That’s why many patients pay out-of-pocket-around $200 to $500 per test. But consider this: one adverse drug reaction can cost over $10,000 in hospital bills. A test that prevents one hospital stay pays for itself.

What’s Changing Fast-And What’s Coming

The field is moving quickly. The FDA is drafting rules to require PGx testing for 12 more drugs by 2025, including statins, SSRIs, and warfarin. The TAILOR-PCI2 trial, now enrolling 6,000 patients across 15 countries, will finally settle whether testing for CYP2C19 before prescribing clopidogrel actually reduces heart attacks. Early studies said yes. The first big trial in 2020 said no. This one will give us the answer.Meanwhile, the NIH’s All of Us program is collecting genetic data from 3.5 million Americans-including people from underrepresented ethnic groups. Right now, 78% of pharmacogenomic studies are based on people of European descent. That means the data for African, Asian, or Indigenous populations is incomplete. That’s changing. Better data means better recommendations for everyone.

And companies are scaling up. Thermo Fisher, Myriad Genetics, and Invitae now offer PGx panels that test for dozens of genes at once. Some health systems, like Mayo Clinic, have preemptively tested over 15,000 patients. They don’t wait for someone to get sick. They test before prescribing-like a vaccine for bad drug reactions.

What You Can Do Today

You don’t need to wait for your doctor to suggest it. If you’ve had bad reactions to medications, if you’ve tried multiple drugs without success, or if you’re about to start a new treatment for depression, pain, or heart disease, ask for pharmacogenomic testing. Bring the research. Ask if your provider has access to CPIC guidelines. Ask if they use a clinical decision support tool like PharmCAT.If your doctor says no, ask for a referral to a clinical pharmacist who specializes in pharmacogenomics. Many hospitals now have PGx consult services. In Australia, some private clinics offer testing with telehealth follow-ups. Costs are dropping. Accuracy is over 99%. And the payoff? Fewer side effects. Fewer hospital trips. Better outcomes.

This isn’t science fiction. It’s medicine catching up to biology. Your genes have been talking to your body all along. Pharmacogenomics is just the first time we’ve learned to listen.

Is pharmacogenomic testing covered by insurance?

Coverage varies. In oncology, nearly 90% of private insurers cover testing. For psychiatric medications, it’s about 47%. For heart drugs or pain medications, coverage is often limited or denied. Medicare and Medicaid rarely cover it unless it’s required by FDA guidelines, like for abacavir. Some private clinics offer self-pay options for $200-$500. Many patients find the cost worth it after avoiding a single hospital visit due to an adverse reaction.

Do I need to get tested if I’m not on any medication?

Not immediately. But if you’re planning to start a new drug-especially antidepressants, painkillers, blood thinners, or heart medications-it’s smart to get tested before you begin. Your results stay with you for life. Once you’ve been tested, your genetic profile can guide future prescriptions, even years down the line. Some people choose to get tested proactively, especially if they have a family history of bad drug reactions.

Can I use 23andMe or other direct-to-consumer tests for pharmacogenomics?

Some 23andMe reports include limited pharmacogenomic data, like CYP2C19 and CYP2D6 variants. But these are not clinical-grade tests. They’re meant for curiosity, not medical decisions. Clinical tests analyze more genes, use validated methods, and come with interpretation from a certified lab and often a pharmacist or genetic counselor. Relying on consumer tests for prescribing decisions can be dangerous. Always confirm results with a clinical-grade test if treatment changes are being considered.

How long does it take to get results?

Most clinical labs deliver results in 7 to 14 days. Some urgent cases, especially in oncology, can get results in 3-5 days. The test itself is fast-a swab or blood draw takes minutes. The delay comes from lab processing and interpretation. Once results are in, your doctor or pharmacist should review them with you and adjust your medication plan accordingly.

Are there risks to getting tested?

The physical risk is minimal-just a swab or blood draw. The bigger risk is psychological: learning you carry a gene variant that increases your risk for a bad reaction can cause anxiety. There’s also the risk of misinterpretation. If results aren’t reviewed by someone trained in pharmacogenomics, you might get incorrect advice. That’s why it’s critical to work with a provider who understands CPIC guidelines and has access to decision-support tools. Privacy is another concern, but under Australian law, genetic data is protected under the Privacy Act and cannot be used to deny insurance.

What’s Next for Personalized Medicine

Pharmacogenomics is just the beginning. Soon, we’ll see polygenic risk scores that combine dozens of genes to predict how you’ll respond to a drug-not just one or two. We’ll see AI tools that match your genetic profile with your medical history to suggest the best treatment option in seconds. We’ll see routine PGx testing built into primary care, like checking blood pressure.But right now, the most powerful thing you can do is ask. If you’ve been through the frustration of trying drug after drug without success, your genes might hold the answer. You don’t need to wait for the system to catch up. You can start the conversation today.

Lauren Wall

January 22, 2026 AT 00:55Finally, someone says it. I’ve been on six antidepressants and each one made me feel like a zombie or a panic attack waiting to happen. My doctor laughed when I asked about genetic testing. Guess what? I paid $350 out of pocket. Turned out I’m a CYP2D6 ultra-rapid metabolizer. Switched to bupropion. I haven’t cried in three months. Stop guessing. Test us.

Tatiana Bandurina

January 24, 2026 AT 00:06Let’s be real. The entire field is overhyped. Only 15-20% of drugs have actionable PGx data. That’s not precision medicine-that’s placebo medicine with a DNA sticker. And don’t get me started on the $500 tests. The real cost isn’t the swab-it’s the systemic waste of time, money, and false hope. We’re turning pharmacology into a lottery.

Philip House

January 25, 2026 AT 05:23It’s funny how Americans act like this is some revolutionary breakthrough. We’ve known for decades that metabolism varies by ethnicity. The CYP2D6 ultra-rapid phenotype is common in East Africans and Middle Easterners. The FDA’s warnings? They’re just catching up to what global medicine has known since the 90s. We didn’t need a $500 test to know codeine kills babies in some populations. We needed better global data collection-and we still don’t have it.

Ryan Riesterer

January 26, 2026 AT 23:37Pharmacogenomic testing is not a diagnostic tool-it’s a pharmacokinetic risk stratification instrument. The clinical utility is context-dependent: high for SSRIs and antiplatelets with validated CPIC guidelines, low for statins and antihypertensives where polygenic contributions dominate. The real bottleneck isn’t the assay-it’s the integration of genotype-phenotype decision trees into EHRs via PharmCAT or similar CDS systems. Without that, you’re just generating noise.

Akriti Jain

January 27, 2026 AT 21:34OMG 😱 so they’re testing our DNA so Big Pharma can charge us more? 🤔 Next they’ll scan our tears to see if we’re ‘emotional enough’ for antidepressants. I bet 23andMe is secretly selling our genes to insurance companies. 😈 They already know if we’re gonna die from a pill before we even take it. Why do you think they don’t want you to know this? #PharmaControl #GeneticSlavery

Mike P

January 28, 2026 AT 16:38Yeah right, like this is some magic bullet. I’ve got a cousin in Texas who got tested after his heart attack. Turned out he was a slow metabolizer for Plavix. Doctor switched him to ticagrelor. Saved his life. But then the insurance company denied the test because it wasn’t ‘medically necessary’ for his age. Meanwhile, they paid $40K for his stent. You think that’s fair? We’re paying for the mess, not the prevention. This isn’t science-it’s capitalism with a lab coat.

Neil Ellis

January 29, 2026 AT 18:54This is the future we’ve been waiting for. Imagine a world where no one has to suffer through three bad drugs before finding one that works. Where a kid doesn’t die because their mom took codeine for a headache. Where your doctor doesn’t guess-they know. It’s not perfect yet, but it’s real. And if you’ve ever felt like your body betrayed you with medication, this is your lifeline. Don’t wait for the system to catch up. Ask. Push. Demand. You deserve better than trial and error.

Alec Amiri

January 30, 2026 AT 05:45So let me get this straight. We’re going to test people’s genes so we can avoid giving them the wrong pills… but we still don’t know why some people get addicted to opioids or why others just don’t respond to anything? This feels like putting a bandaid on a broken leg and calling it medicine. We’re treating symptoms, not causes. And we’re charging people $500 to do it.

Lana Kabulova

January 31, 2026 AT 04:31Wait-so if I’m a CYP2C19 poor metabolizer, I can’t take clopidogrel? But what if I can’t afford ticagrelor? What if I live in a state where Medicaid won’t cover the test? And what if my doctor doesn’t even know what CYP2C19 means? This isn’t personalized medicine-it’s a privilege for people who can afford to be right. And don’t even get me started on how this excludes non-European populations…

Rob Sims

February 1, 2026 AT 07:04Oh wow, genetic testing? That’s so 2020. Everyone knows the real issue is that doctors don’t listen. I had a pharmacist tell me my antidepressant wasn’t working because I was ‘noncompliant.’ Turns out I was a CYP2D6 ultra-rapid. The test cost $200. The doctor’s apology? A free sample of another drug that didn’t work either. This isn’t science. It’s a joke with a lab report.

Patrick Roth

February 1, 2026 AT 20:43Actually, the whole premise is flawed. If genes were so decisive, why do identical twins often respond differently to the same meds? Epigenetics, environment, gut microbiome-all matter more than a few SNPs. This is genetic reductionism dressed up as innovation. We’re ignoring the complexity of human biology for the sake of a marketable test. The science is interesting-but it’s not the solution everyone thinks it is.

shivani acharya

February 2, 2026 AT 05:49Let me tell you what they’re really hiding. The government doesn’t want you to know this because if everyone got tested, they’d realize that 80% of psychiatric meds are useless for most people. They’d see that Big Pharma spent billions marketing drugs that only work for 1 in 5. And if we all knew our genes? We’d stop taking their pills. They’d lose billions. So they keep the tests expensive, the doctors untrained, and the public confused. It’s not about medicine-it’s about control. And they’re using your suffering to keep the money flowing. I’ve seen it. I’ve read the emails. Don’t trust the system.

Sarvesh CK

February 3, 2026 AT 23:35While the potential of pharmacogenomics is undeniably transformative, its implementation must be approached with humility and systemic awareness. The reduction of drug response to discrete genetic variants risks overlooking the intricate interplay of environmental, cultural, and socioeconomic determinants of health. For instance, in low-resource settings, access to consistent medication, nutritional status, and stress levels may exert greater influence on therapeutic outcomes than CYP2D6 polymorphisms alone. Therefore, while genetic insights are invaluable, they must be integrated-not as a panacea, but as one component within a broader, equity-centered model of care.

Margaret Khaemba

February 4, 2026 AT 21:41I’m a nurse in rural Ohio. We don’t have genetic counselors. Most patients can’t afford the test. But I’ve started asking: ‘Have you ever had a bad reaction to a med?’ If yes, I write it down. I tell them: ‘Your story matters. Your body remembers. Write it down. Bring it to your next appointment.’ Sometimes that’s all we have. And sometimes… that’s enough. You don’t need a lab to know your body’s telling you something. Just listen.