When you hear about colorectal polyps, it’s easy to assume they’re all the same. But that’s not true. Two main types-adenomas and serrated lesions-drive most cases of colorectal cancer, and they behave very differently. Knowing the difference isn’t just academic; it affects how often you need screenings, how carefully your doctor looks during a colonoscopy, and what happens after a polyp is removed.

What Are Adenomas, and Why Do They Matter?

Adenomas are the most common precancerous polyps, making up about 70% of all polyps found during colonoscopies. They start as small, benign growths on the colon lining but can slowly turn into cancer over 10 to 15 years if left alone. Not all adenomas are equal, though. Their structure determines how dangerous they are.

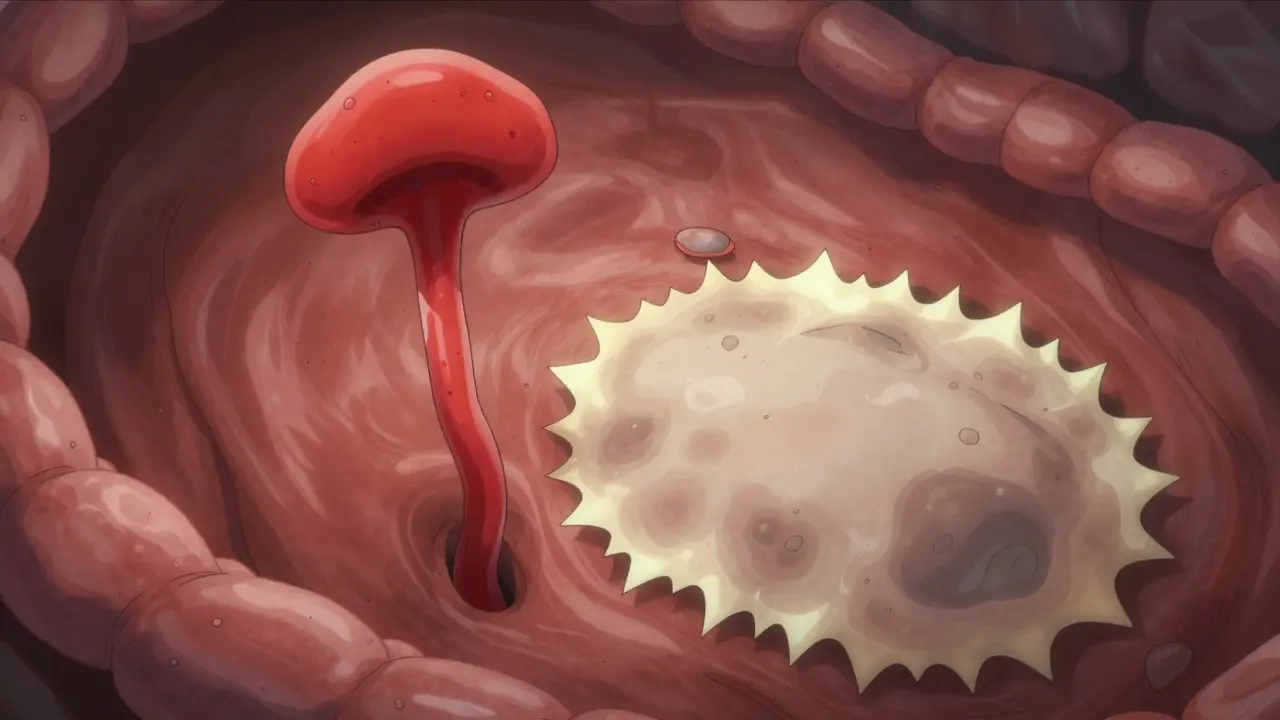

Tubular adenomas are the most common type-about 70% of all adenomas. These are usually small, round, and grow like little mushrooms on a stalk. They’re the easiest to remove and carry the lowest cancer risk. If one is under half an inch (1.27 cm), the chance it already contains cancer is less than 1%.

Tubulovillous adenomas are less common, making up about 15% of adenomas. They mix tubular and villous features. Villous adenomas, the remaining 15%, are flatter and spread out like a carpet over the colon wall. These are harder to remove completely and carry a much higher risk. Once they grow larger than 1 cm, the chance of cancer inside jumps to 10-15%. The more villous tissue they have, the worse the risk. A villous component can increase cancer likelihood by 25-30% compared to a purely tubular polyp of the same size.

Serrated Lesions: The Stealthy Path to Cancer

Serrated lesions are less common but just as dangerous. They account for 20-30% of all colorectal cancers, according to Gastro Health Partners. Unlike adenomas, they don’t grow in a neat, mushroom-like shape. Under the microscope, they look like a saw blade-hence the name “serrated.”

There are three types:

- Hyperplastic polyps: These are usually harmless, especially if they’re small and found in the lower colon. They rarely turn cancerous.

- Sessile serrated adenomas/polyps (SSA/Ps): These are the real concern. They’re flat, often hidden in the upper colon (cecum or ascending colon), and easy to miss during colonoscopy. They grow slowly but can turn into cancer through a different biological path than adenomas. Studies show they have the same cancer risk as conventional adenomas-around 13% develop high-grade dysplasia or cancer.

- Traditional serrated adenomas (TSAs): These are rarer but aggressive. They often appear in the left colon and can turn cancerous faster than SSA/Ps.

What makes SSA/Ps so tricky? They’re flat or slightly raised, not polypoid. Most colonoscopies miss them because they blend into the colon wall. One study found that 2-6% of sessile polyps go undetected during routine exams. And because they’re often in the right side of the colon-where the bowel is wider and harder to see-they’re even harder to catch.

How Are They Detected? And Why It’s So Hard

Not all polyps are created equal when it comes to visibility. Pedunculated polyps-those with a stalk-are easy to spot and remove. Sessile and flat polyps? Not so much.

SSA/Ps are particularly sneaky. They often have a pale color, a mucus cap, and subtle borders. Under magnifying colonoscopy, they show distinctive features: round or open pit patterns, expanded crypt openings, and twisted blood vessels. But without high-definition imaging and expert eyes, they look like normal tissue.

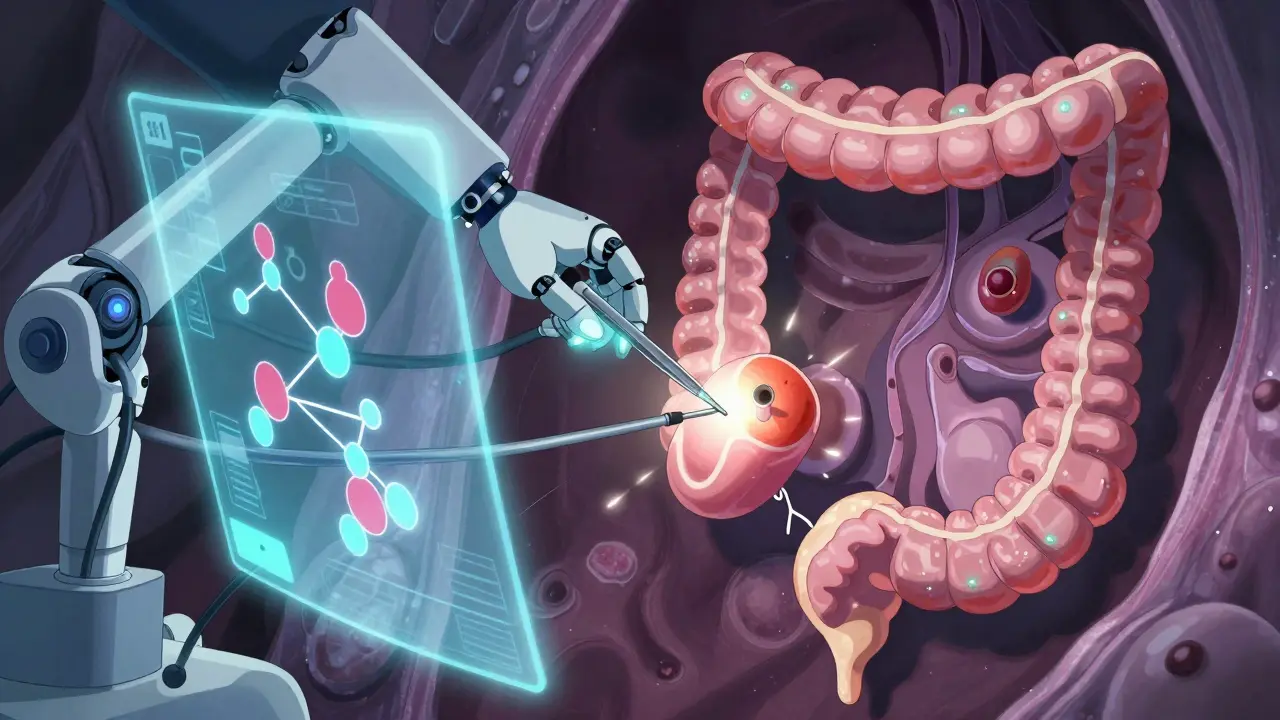

That’s why newer tools matter. In 2022, the FDA approved AI-assisted colonoscopy systems like GI Genius. In clinical trials, these systems boosted adenoma detection by 14-18%. That’s huge. It means more SSA/Ps and adenomas are found the first time, reducing the chance you’ll need a repeat colonoscopy because something was missed.

Still, detection isn’t perfect. Even the best colonoscopies miss up to 6% of polyps. That’s why the quality of the prep-how clean your colon is-and the experience of the endoscopist make a big difference.

Removal and Follow-Up: What Happens After the Polyp Is Gone?

Once a polyp is found, it’s removed during the colonoscopy. This is called a polypectomy. For small adenomas under 2 cm, success rates are 95-98%. But for larger SSA/Ps-especially those over 2 cm-the success rate drops to 80-85%. Why? Because they’re flat. It’s harder to lift them off the wall without leaving pieces behind.

That’s why complete removal is critical. If even a tiny bit is left, it can regrow and turn cancerous. That’s why doctors often mark the site with a tattoo or take extra biopsies after removal.

After removal, surveillance isn’t one-size-fits-all. The American Cancer Society and other groups agree: if you had an adenoma or a serrated lesion, you’re at higher risk for future polyps. But how often you need a follow-up colonoscopy depends on the type, size, and number of polyps.

Here’s what current guidelines say:

- If you had one or two small tubular adenomas (<1 cm), next colonoscopy in 7-10 years.

- If you had three to ten adenomas, or any adenoma larger than 1 cm, next colonoscopy in 3 years.

- If you had an SSA/P ≥10 mm, most U.S. guidelines recommend a 3-year follow-up. But some European guidelines say 5 years-because progression may be slower in those populations.

- If you had a TSA, follow-up in 3 years, no matter the size.

There’s no universal rule. Your doctor will weigh the number, size, and type of polyps-and your family history-to set your schedule.

Molecular Differences: Why Two Paths to Cancer?

It’s not just about how polyps look. They grow through different biological pathways.

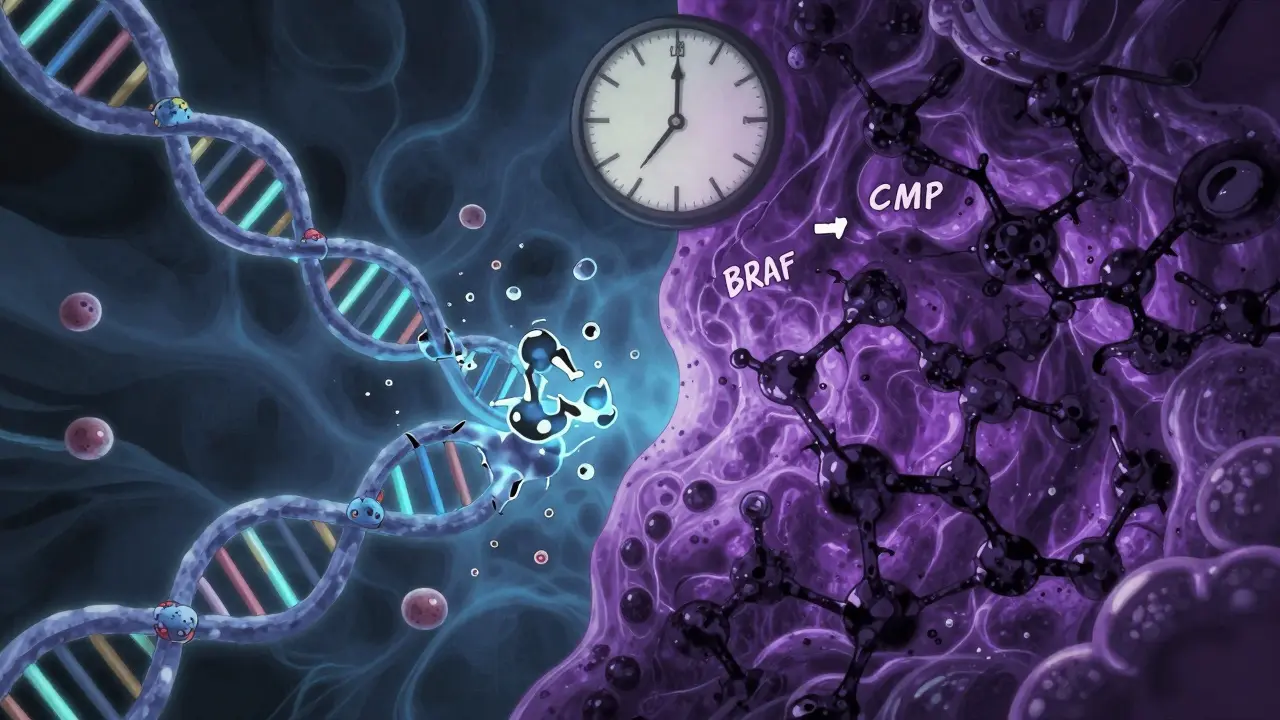

Adenomas usually follow the chromosomal instability pathway. That means they start with a mutation in the APC gene, then accumulate more DNA errors over time. This is the classic “adenoma-carcinoma sequence” taught in medical school.

Serrated lesions, especially SSA/Ps, follow the serrated pathway. They start with a BRAF gene mutation and show something called CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP). This means their DNA gets heavily “methylated”-a chemical change that silences tumor-suppressing genes. This pathway can skip the adenoma stage entirely and jump straight to cancer.

This matters because it explains why some people get cancer even after a “clean” colonoscopy. If a serrated lesion was missed, it could turn cancerous in as little as 5 years-much faster than the 10-15 years typical for adenomas.

What You Need to Know: Real-World Implications

Here’s the bottom line:

- Most polyps aren’t cancer. But they can become cancer if not removed.

- Adenomas are common. Serrated lesions are rarer but just as dangerous.

- Size matters. Larger polyps = higher cancer risk.

- Location matters. Right-sided polyps (SSA/Ps) are harder to see.

- Removal is effective-but only if it’s complete.

- Follow-up colonoscopies save lives. Skipping them increases your risk.

Studies show people who’ve had any type of precancerous polyp have a 1.5 to 2.5 times higher risk of developing colorectal cancer later. But here’s the good news: most people with these polyps never get cancer. That’s because we can find and remove them early.

Screening works. Between 2010 and 2020, colorectal cancer rates dropped 3% per year in adults over 55 thanks to better screening and polyp removal. But in adults under 50, rates are rising-by 2% per year. That’s why guidelines now recommend starting screening at age 45, not 50.

And the future? Molecular testing of polyps is coming. Within five years, doctors may be able to test a removed polyp for specific gene mutations and tell you exactly how often you need a colonoscopy-not just based on size and shape, but on your personal biology.

What If You Have No Symptoms?

That’s the point. Most people with polyps feel fine. No pain. No bleeding. No changes in bowel habits.

But when symptoms do show up, they’re often late signs: rectal bleeding (in 30-40% of cases), iron-deficiency anemia (15-20%), or changes in stool shape or frequency. By then, the cancer may already be advanced.

That’s why screening isn’t about waiting for symptoms. It’s about catching the problem before it becomes one.

Phil Maxwell

January 23, 2026 AT 01:17Been through a couple colonoscopies myself. The prep is the real villain, not the polyps. Once they find one, you just kinda accept it’s part of getting older. Glad they’re catching more now with the AI stuff. Feels like the docs are finally catching up to the tech.

Still, I wish they’d just tell you upfront how often you’ll need to go back. No one likes surprises when your butt’s on the line.

Dolores Rider

January 23, 2026 AT 23:00THEY’RE LYING TO US. 😱

They say adenomas turn to cancer in 10-15 years... but what if they’re just hiding the fact that the dye they use during colonoscopies is what’s causing the mutations?? I read a guy on TruthTube who said the FDA banned the stuff in 2019 but it’s still being used in 80% of clinics. THEY’RE PROFITING OFF YOUR FEAR.

Also, why do they always take biopsies from the RIGHT side? Coincidence? I think not. 👁️

venkatesh karumanchi

January 24, 2026 AT 12:27This is such an important post. In India, most people still think colon cancer only happens to old men who eat too much meat. But I’ve seen young patients with SSA/Ps-no family history, no bad habits. It’s scary how silent these polyps are.

Thank you for explaining the difference between adenomas and serrated lesions. Many doctors here still call everything ‘polyps’ and don’t know the subtypes. Knowledge saves lives.

Let’s spread this info. More awareness = fewer late-stage diagnoses.

Kat Peterson

January 25, 2026 AT 23:33OMG I just realized I’ve been reading ‘serrated’ like ‘serated’ this whole time 😭

And now I’m traumatized. Like, I thought it was just a typo in the article, but nooo-it’s a saw blade?? In my COLON??

Also, who decided ‘sessile’ was a good word to use? It sounds like a bad perfume. 🤢

Anyway, I’m scheduling my colonoscopy. And I’m bringing a pillow. And maybe a priest.

Also, AI? Really? So now robots are looking at my insides?? Are they judging me?? 😭

Josh McEvoy

January 27, 2026 AT 10:41bro i had a polyp removed last year and they told me to come back in 5 years

i asked if i could just skip it

they said ‘no’

i said ‘but i feel fine’

they said ‘that’s the problem’

so now i’m just waiting for the apocalypse

also why do they always use the word ‘surveillance’ like i’m a spy?? 😂

Viola Li

January 28, 2026 AT 22:15Everyone’s acting like this is some groundbreaking revelation. Newsflash: colon cancer has been around since humans had intestines. You think the FDA is suddenly going to care about your ‘serrated lesions’ because some doctor wrote a blog post?

Meanwhile, 40% of Americans can’t afford a colonoscopy. But sure, let’s all panic about AI detection while people skip screenings because they can’t take a day off work.

Stop pretending this is about health. It’s about profit. And fear. And overpriced medical jargon.

Jenna Allison

January 30, 2026 AT 17:26For anyone confused about the difference between SSA/Ps and tubular adenomas: think of it like two different types of weeds.

Tubular = dandelions. Easy to pull, you see them coming.

SSA/P = crabgrass. Flat, sneaky, blends in, grows under the surface. You don’t notice until it’s taken over half your lawn.

And yes, the AI tools are a game-changer-studies show they catch 20% more SSA/Ps in the right colon, which is where most get missed. The key is high-quality prep. If your colon isn’t clean, even AI can’t help.

Also: if your doc doesn’t mention ‘pit patterns’ or ‘mucus caps,’ ask them if they use high-definition scopes. Most don’t.

Vatsal Patel

January 30, 2026 AT 22:48Ah yes, the modern miracle of medical capitalism.

You have a colon. It grows polyps. Now you must pay to have them removed. Then pay to come back. Then pay for AI. Then pay for the biopsy. Then pay for the follow-up. Then pay for the anxiety.

And all this because nature, in its infinite wisdom, decided to make cancer grow like a silent ghost in the dark.

But hey, at least we have emojis now. 🤡

Question: if a polyp grows in a colon and no one sees it… does it still turn into cancer? Or does it just… sigh and fade away, disappointed in humanity?

John McGuirk

January 31, 2026 AT 17:09They’re not telling you the whole story. Why? Because they don’t want you to know that the real cause of these polyps isn’t genetics or diet-it’s the fluoridated water. Every single one of these ‘serrated lesions’ is linked to fluoride exposure. The WHO knew in 1992. They buried it.

And now they want you to pay $3000 for a colonoscopy with ‘AI assistance’? HA. That’s just a fancy way to scan your colon for fluoride buildup.

Drink distilled water. Stop trusting doctors. And for god’s sake, stop eating processed food. (But don’t tell them I said that.)

Michael Camilleri

January 31, 2026 AT 19:04So we’re supposed to believe that a flat polyp in your right colon is somehow more dangerous than a mushroom-shaped one in the left? Sounds like a marketing gimmick to me.

Also why do they always say ‘high-grade dysplasia’ like it’s a bad thing? Isn’t dysplasia just your body trying to adapt? Maybe it’s not cancer… maybe it’s evolution.

And who decided 10-15 years is the timeline? Did they time it with a stopwatch? I think they just picked a number that sounds scientific.

Meanwhile I’m over here eating bacon and wondering if my colon is judging me.

Also I spelled ‘colonoscopy’ wrong on my last insurance form. They didn’t notice. Maybe that’s the real solution.